Population Control & Policymaking: A Lesson from the Emergency

- IPC

- Jun 26, 2020

- 19 min read

An excerpt from Gyan Prakash’s Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point outlines the questionable lineage of flawed and problematic policies, whose effects were exacerbated during the Emergency.

If this were 1975, today would be the first ‘day’ of the dreadful Emergency (it was declared shortly before midnight on the 25th of June). If you ask someone to name some of the Emergency’s worst excesses, forced sterilizations will be near the top of many people’s lists, close on the heels of unlawful arrest, torture and extrajudicial killing. But, as Gyan Prakash notes in the excerpt below (a subchapter titled 'The Prehistory of Turkman Gate: Population Control'), “not only did these programs (such as population control and slum clearance for urban ‘beautification’) predate the Emergency but so did the deployment of coercion.”

Prakash traces the ancestry of the Emergency’s population control measures back to the late 1700s in the West and to the 1930s in India. Further, he tracks the influence of the developed world’s perspective - as well as its aid and support - on our population control policy so that “even without being explicitly intended, coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor.”

It is rare to find thorough histories of policymaking, especially Indian policymaking, and the following excerpt may prove to be eye-opening in many ways, as well as inform us of the kind of errors we need to be watchful about in the future.

The Prehistory of Turkman Gate: Population Control

In the post-Emergency discourse, Turkman Gate became a defining emblem of the tyranny of 1975–77. A spate of books published after the end of the Emergency cited the coercive sterilization and slum clearance drives in the Walled City as conclusive proof of the regime’s brutality. The opposition successfully turned nasbandi (vasectomy) into the symbol of the Emergency’s cruelty in the March 1977 elections to depose Indira Gandhi. The Shah Commission instituted by the Janata government in May 1977 to inquire into the Emergency’s “excesses” also helped consolidate the discourse that coercive population control and slum clearance drives broke from the normal exercises of power. It documented the forcible imposition of family planning programs on the population as one of the Emergency’s “excesses,” regarding it as sharply different from the “voluntary” practices in the preceding period.

Undoubtedly, Sanjay’s aggressive advocacy of population control and slum clearance for “urban beautification” drove them into high gear. But not only did these programs predate the Emergency but so did the deployment of coercion. Let us turn first to population control.

As Mathew Connelly has shown, the objective to limit family size in India not only went back decades before the Emergency but actually originated as a global project. Thomas Malthus fired the opening shot with the publication of his Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. It laid out an apocalyptic future in which population growth would outstrip food supply, with only famines and wars acting to maintain the balance. When Asians and Africans also began to live longer and grow in numbers in the twentieth century, European and North American elites began to worry about “the rising tide of color” and the impending “yellow peril.” The concern was that the poorest and the least capable would soon outnumber the fittest and the best.

The late-nineteenth-century development of the science of demography gave concrete shape to these worries. Legible in numbers, people became “population,” which had to be managed. Connelly advisedly uses “population control” rather than “family planning” to describe this project. The “term family planning, in the sense of promoting reproductive rights, means the opposite of population control.” Instead of rights, nutrition, and overall well-being of the family, it means a narrower set of policies and programs aimed at achieving and manipulating population growth targets. Sharing these objectives, a movement developed out of the activities of the eugenicists, Malthusians, pro-natalists, and birth control and public health advocates, who pushed for population control with a diversity of motives.

Undoubtedly, Sanjay’s aggressive advocacy of population control and slum clearance for “urban beautification” drove them into high gear. But not only did these programs predate the Emergency but so did the deployment of coercion.

Beginning with a concern about the growth of the human species outstripping natural resources, the population control movement took on a planetary perspective. It made the biological process of reproduction a branch of history, subject to human control on a world scale. Even concerns within nation-states about immigration and its effect on the social composition of the citizenry drew on the differential racial growth of the world population. Government leaders, scientists, and population control activists “thought globally” in pressing for new reproductive norms and devising campaigns to control population.

An indefatigable campaigner for global population control was Margaret Sanger. The founder of the American Birth Control League, the precursor of Planned Parenthood, Sanger famously traveled to Wardha to meet Mahatma Gandhi to convince him of the value of birth control. While Gandhi shared the goal of limiting births, he steadfastly stuck to his idea that sex without reproduction was sin. For him, only abstinence, not birth control, was the approved method to limit procreation. Undaunted, Sanger pressed on with her efforts to establish birth control clinics in the country in the 1930s.

Like their international counterparts, Indian elites became concerned about population growth. While one Brahman advocate of Sanger’s birth control mission argued, unsupported by data, that lower castes and Muslims procreated at a higher rate, another called for either voluntary or coercive sterilization. Gyan Chand, a professor of economics in Patna University, published India’s Teeming Millions in 1939, followed five years later by The Problem of Population, arguing that reducing the birth rate was crucial for reducing poverty and misery. Radhakamal Mukherjee, a professor of economics and sociology at Lucknow University, was another key figure in setting the tone for the population discourse in the nationalist economic policy community. He founded the Indian Population Conference in 1936 and wrote Food Planning for 400 Millions in 1938, which recommended that population growth be brought in line with national production. Mukherjee went on to head the subcommittee on population of the Congress party’s National Planning Committee.

In a report in 1940, the planning committee warned that the “disparity in the natural increase of different social strata shows a distinct trend of mispopulation.” It cautioned that the greater likelihood of upper classes and advanced castes practicing contraception was leading to the “gradual predominance of inferior social strata.” The report urged the removal of barriers to intermarriage among upper castes and the dissemination of birth control propaganda among the masses to avert “deterioration of the racial makeup.” Nehru, who chaired the committee, endorsed population control while also recommending other measures such as improved nutrition so that the poor would cease using a high birth rate to hedge against high infant mortality. The National Planning Committee finally recommended broad economic development as a national goal as well as reducing population pressure.

In a report in 1940, the Congress party’s National Planning Committee warned that the “disparity in the natural increase of different social strata shows a distinct trend of mispopulation.” It cautioned that the greater likelihood of upper classes and advanced castes practicing contraception was leading to the “gradual predominance of inferior social strata.” The report urged the removal of barriers to intermarriage among upper castes and the dissemination of birth control propaganda among the masses to avert “deterioration of the racial makeup.”

The Indian elite discourse on population was in line with the global project that made rapid strides after World War II. With the world population growing in spite of the devastating war, researchers invoked the “demographic transition” theory to advance policies to limit the birth rate globally. A leading figure in formalizing and globalizing the idea of demographic transition was Frank Notestein, who founded the Office of Population Research at Princeton University in 1936 to offer graduate training in demography. Building on his study of Europe and the Soviet Union, he offered the demographic transition as a theory to explain and manage the rising population in the developing world. According to him, societies moved from high to low birth and death rates in discrete stages, which correlated to successive phases of modernization. Applying this theory, the Office of Population Research under Notestein internationalized demography, initiating studies of the world population, and sponsored Kingsley Davis’s influential The Population of India and Pakistan (1951), which proposed control over reproduction as the critical battleground against poverty.

For population and development activists, frequently one and the same, the mantra was modernization, and the small family was its embodiment and instrument. Notestein was at the center of this activism. Partly because of his advocacy, the United Nations established its Population Division in 1946, with Notestein as its first director. UN agencies like the Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization became eager partners as UN officials saw population policy as a step toward the global governance of population. An international population policy establishment rapidly took shape after 1952 with the founding of the Population Council by John D. Rockefeller. The council brought together the International Planned Parenthood Foundation (IPPF), the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, and pharmaceutical companies, becoming a network for the major actors in the field.

India was the most important country for population activists, and the key driver of the project was the Ford Foundation under its Delhi chief, Douglas Ensminger. The foundation’s promotion of modernization was part of the anti-communist U.S. agenda against the Soviet Union, but Ensminger skillfully delinked Ford India from Cold War geopolitics and positioned it as India’s partner in a broad strategy of development. The agreement establishing Ford’s India field office at Nehru’s invitation stated that the foundation would assist in initiating programs deemed urgent by the Indian government but delayed by routine budgetary procedures. Additionally, Ford would provide the resources required to test methods of development for which the government could not readily release funds. This agreement aligned Ford with Indian government programs, projecting the foundation only as a source of technical advice and financial assistance for projects initiated and run by Indians.

Population control, which was already part of India’s First Five-Year Plan, was high on Ensminger’s list of priorities. Accordingly, he approached Nehru, who needed no convincing about the need for restraining population growth. But he expressed his government’s inability to act without Health Minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur getting on board. Kaur was a leader of some stature. Belonging to a Punjabi royal family, she had gone to school in England, had graduated from Oxford, and became an activist in the nationalist struggle and Gandhi’s follower on her return to India. After Independence, she was one of two Christians, and the only woman, inducted into Nehru’s first cabinet. As a Gandhian, she was prickly about sex unmotivated by procreation implied by the birth control program.

India was the most important country for population activists, and the key driver of the project was the Ford Foundation under its Delhi chief, Douglas Ensminger… he approached Nehru, who needed no convincing about the need for restraining population growth. But he expressed his government’s inability to act without Health Minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur getting on board. Kaur was a leader of some stature. Belonging to a Punjabi royal family, she had gone to school in England, had graduated from Oxford, and became an activist in the nationalist struggle and Gandhi’s follower on her return to India. After Independence, she was one of two Christians, and the only woman, inducted into Nehru’s first cabinet. As a Gandhian, she was prickly about sex unmotivated by procreation implied by the birth control program.

Undeterred, Ensminger set to work. In March 1955, he sought an appointment with her and began the meeting by saying that while he wanted to talk about family planning, he would not if she so wished. Disarmed, she asked him to present his views. Finding his opening, Ensminger went on to speak about the relationship between population growth and mass poverty and that it was their duty to help all those who sought help in limiting their families. After an hour of their exchange, Kaur asked if he could arrange for experts who could help her think through the issue and formulate policies. Ensminger was prepared. Planning ahead, he had already obtained a promise from John D. Rockefeller III in New York to personally pay for two consultants to come to India so that they did not appear to be representing either the Ford or Rockefeller Foundation but were simply experts in the field. So, when Kaur asked for expert advice, Ensminger readily agreed, knowing he could deliver. Accordingly, Leona Baumgartner, the head of New York Public Health Services, and Frank Notestein of Princeton University visited Delhi and helped formulate the health minister’s first policy statement on population control.

The report submitted by Baumgartner and Notestein to Health Minister Kaur encouraged the government to boost its family planning efforts with sustained research and field trials to gain knowledge on different contraceptive methods, cultural preferences, and demographic patterns. Its most important recommendation was the establishment of a semiautonomous family planning body within the Health Ministry to formulate policies and coordinate their implementation. The government heeded the advice and established the Central Family Planning Board in 1956, with Colonel B. N. Raina of the Army Medical Corps at its head. Population control also received high priority in the Second Five-Year Plan, which commenced in 1956. It allocated a budget of nearly 50 million rupees to the new board and created advisory boards at the center and in the states. The vigorous push for population control included devising a flexible system of financial assistance to the states and a call for establishing family planning clinics nationwide, offering contraceptive services. Ford made its first major grant of $300,000 in 1959 to the Health Ministry and went on to provide substantial financial assistance in subsequent years to pay for training Indian personnel, research, pilot projects, fellowships, consultants, drugs, and equipment and supplies. The Third Five-Year Plan (1961–66) ramped up the family planning budget to 270 million rupees, over five times the Second Plan’s allocation. Ford proposed assistance of $12 million, though its board eventually approved only $5 million, which was still a substantial increase in its commitment. This was to fund a number of new programs, institutions, consultants, and training schemes.

By the mid-1960s, Ford was burrowed so deep into the Indian government’s family planning programs that a Population Council staff member noted in 1965 that he had encountered several Indians who contend that the “government does whatever the Ford Foundation says it should do in Family Planning.” With 72 expatriate professionals, 177 Indian technical and administrative staff, 63 assorted full-time employees, and 16 foreign individuals in various institutions supported with funds, Ensminger developed Ford in India as the largest foreign foundation presence anywhere in the world. It provided the ideas and funds for many of the government family planning programs and organizations, its consultants were planted in the Health Ministry, and the foundation arranged for family planning officials to visit New York. It vigorously promoted and assisted the distribution of the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD or the loop) and mass marketing of the low-priced condom Nirodh (protection). With a strong belief in communications, Ford also employed a consultant who devised an advertising program using a female elephant. She was named Lal Tikon, or the Red Triangle, the symbol of family planning. She would go from village to village, distributing leaflets with her trunk with information on family planning and condoms. On one side she sported a colorful image of the Red Triangle and a happy couple with the words (in Hindi): “You don’t need another child now—Don’t ever have another after three.” On the other side was another Red Triangle with the words: “My name is Red Triangle—My job is spreading happiness.”

It was one thing to advertise and educate but quite another to get people to come to the clinic and take advantage of the contraceptives being offered. Recognizing the problem, the Third Plan had shifted to an “extension approach” that called for the population control program to seek out people rather than wait for them to come to clinics. As the head of the Family Planning Board, it was up to Colonel Raina to lead the new effort. Associated with the population control movement since 1937, he brought optimism and energy to his position, a quality that Ford officials appreciated; some in the Population Council, however, worried that the colonel cared more for jeeps, equipment, and dollars for the program than “real research.”

By the mid-1960s, Ford was burrowed so deep into the Indian government’s family planning programs that a Population Council staff member noted in 1965 that he had encountered several Indians who contend that the “government does whatever the Ford Foundation says it should do in Family Planning.” With 72 expatriate professionals, 177 Indian technical and administrative staff, 63 assorted full-time employees, and 16 foreign individuals in various institutions supported with funds, Ensminger developed Ford in India as the largest foreign foundation presence anywhere in the world. It provided the ideas and funds for many of the government family planning programs and organizations, its consultants were planted in the Health Ministry, and the foundation arranged for family planning officials to visit New York. It vigorously promoted and assisted the distribution of the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD or the loop) and mass marketing of the low-priced condom Nirodh (protection).

A man of action, Colonel Raina directed every village and town to form a family planning committee and arranged for “natural group leaders” to be paid an honorarium of a thousand rupees to develop a “small family norm” among their communities. Furthermore, mobile vasectomy camps, anticipating the practices during the Emergency, appeared in Maharashtra, which was held up as an example for other states. Sterilizing men rather than women was the preferred option because a surgeon could carry out the operation within fifteen minutes under local anesthesia. The camps were organized in a carnival-like atmosphere to build group pressure. Heartened by the 172,000 sterilizations performed in 1962, 70 percent of them on men, the Ministry of Health began encouraging the use of mobile vans as a more effective way to reach and sterilize patients institutionalized for tuberculosis, leprosy, and mental illness. By 1965, Colonel Raina was writing an enthusiastic report to John D. Rockefeller III, the chair of the Population Council in New York, about the successes of the government’s family planning program. Rockefeller was taken aback, for he had not asked for a report, nor did he know the colonel, but Raina was fervent about his mission and knew who the international players were.

By 1965, Colonel Raina was writing an enthusiastic report to John D. Rockefeller III, the chair of the Population Council in New York, about the successes of the government’s family planning program. Rockefeller was taken aback, for he had not asked for a report, nor did he know the colonel, but Raina was fervent about his mission and knew who the international players were.

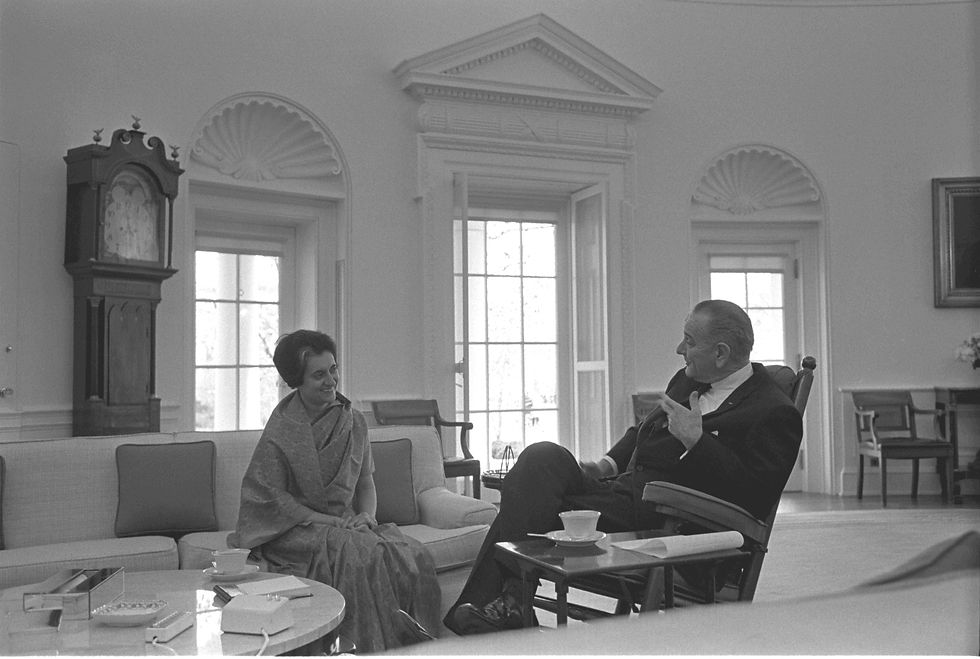

The American proponents of population control found a sympathetic ear in Indira Gandhi. Her family’s ancestral home in Allahabad, Anand Bhawan, came to house a family planning institute. When she was information and broadcasting minister in the Lal Bahadur Shastri government, she pushed for a program to distribute transistor radios in the countryside to broadcast the family planning message. She also pressed her health minister, Sushila Nayar, to adopt the policy of offering financial incentives to women for IUD insertions. When she took over as prime minister in 1966, the Ministry of Health was renamed the Ministry of Health and Family Planning, with a separate department, a secretary, and a minister of state. During her visit to the United States, population control came up in her discussions with President Lyndon Johnson over food aid. Although no record exists of their conversations, Johnson reported that the Indian government had agreed that food and population problems were intertwined. Soon after she returned from Washington, Indira accepted a report from a committee recommending policies to reverse a decline in IUD insertions. Clearly the Americans had used foreign aid as leverage in pressing population control.

For international population control zealots, India’s failure to drastically cut its birth rate was a cause for panic. Paul Ehrlich set the anxious tone in his 1968 international best seller, Population Bomb:

I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi a couple of years ago… The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people.

If Ehrlich sounded the ticking time bomb theory, Indian officials were adopting the metaphor of war in approaching population control. Planning Minister Asoka Mehta, who was later imprisoned during the Emergency and would rail against Indira’s tyranny, could not be clearer about the war at hand and what it required. Population growth is “the enemy at the gate. . . . It is war we have to wage, and as in all wars, we cannot be choosy, some will get hurt, something will go wrong. What is needed is the will to wage the war so as to win it.” He teamed up with other ministerial colleagues in the cabinet to sideline Sushila Nayar, who was clearly not an enthusiastic population warrior. Indira replaced her in 1967 with the demographer Sripati Chandrasekhar, who wished to make sterilization compulsory for every man with more than three children. The cabinet did not go along with this recommendation, but his proposal signaled the direction in which the wind of population control was blowing.

In 1966, New Delhi formally accepted as policy what the Population Council, IPPF, the Ford Foundation, and the World Bank had been recommending: financial incentives for sterilization and IUD insertions. Every state was to be provided with 11 rupees for every IUD insertion, thirty rupees for every vasectomy, and forty for a tubectomy (later increased to ninety rupees), from which they could allocate whatever they deemed fit to individuals, staff, and “motivators.” The number of sterilizations and IUD insertions spiked. Bihar, which had previously had the lowest number of per capita sterilizations and had met only 12 percent of its target for IUD insertions, saw 100,000 people come forward in 1966–67. The next year, the figure jumped to 200,000, with an overwhelming majority opting for sterilization that offered a higher payment. The key factor was the Bihar Famine of 1966–67, which drove the poor to sterilization camps. It was the same story in Madhya Pradesh where the number of people who opted for sterilization jumped from 130,000 in 1966–67 to 230,000 the following year, which was the third year of continuous drought. The experiences in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Orissa were the same. The UP administration directed the family planning officials to report directly to district magistrates, who were pressured to ensure that the staff met targets.

Several states that were not stricken by drought also pursued coercive campaigns. Kerala and Mysore began barring maternity leave to government employees with three or more children; Maharashtra proposed denying medical treatment and maternity benefits to families who had three or more children and recommended making sterilization mandatory for them. Haryana and UP expressed their intent to adopt similar policies. Asoka Mehta acknowledged that such measures had “an element of inhumanity.” But, he continued, “here we have to wield the surgeon’s knife. It may hurt a little, at a point, for a while, but it will help to impart health.”

Planning Minister Asoka Mehta, who was later imprisoned during the Emergency and would rail against Indira’s tyranny, could not be clearer about the war at hand and what it required. Population growth is “the enemy at the gate. . . . It is war we have to wage, and as in all wars, we cannot be choosy, some will get hurt, something will go wrong. What is needed is the will to wage the war so as to win it.” … Kerala and Mysore began barring maternity leave to government employees with three or more children; Maharashtra proposed denying medical treatment and maternity benefits to families who had three or more children and recommended making sterilization mandatory for them. Haryana and UP expressed their intent to adopt similar policies. Asoka Mehta acknowledged that such measures had “an element of inhumanity.” But, he continued, “here we have to wield the surgeon’s knife. It may hurt a little, at a point, for a while, but it will help to impart health.”

In spite of financial incentives and disincentives, sterilizations and IUD insertions were beginning to decline by 1969. Ensminger, who was to leave New Delhi in 1970 after a successful nineteen-year tenure of promoting Ford programs, among which population control occupied a central place, was worried about the overall state of its progress. He wrote to the health minister in July 1969, forwarding a consultant’s report on strengthening the government’s program on family planning. It stressed enhanced training of the family planning staff and the use of incentives as motivation. An interim Ford report a year later rang the population alarm bells loudly, warning that a whopping addition of 130 million projected for the decade to the already existing 540 million would crush the economy. The government effort was laudable but unequal to the task. The report concluded by speculating on the use of compulsory sterilizations, as well as the use of taxation and property regulations to achieve targets: “While some of these measures may seem harsh or punitive, the magnitude of the task ahead, the crucial role that population plays in the entire developmental scheme and the urgency of the problem may well warrant action along these lines.”

In fact, this was where India’s population control policies were headed starting in 1971. It started holding vasectomy camps consisting of mobile field hospitals, which were preceded by sustained propaganda. The number of male sterilizations spiked from 1.3 million in 1970–71 to 3.1 million in 1972–73. Behind the achievement of these impressive numbers was the allocation of targets and the lead taken by district authorities to mobilize the subordinate bureaucracy and the health staff in mobile camps.

Marika Vicziany has shown that the Emergency did not invent coercion. Force was inherent in the pre-Emergency use of financial incentives and disincentives, the employment of motivators, and the mobilization of district officers. Contrary to the “myth” that India was a “soft state” that relied on voluntarism for population control, she shows that the program was coercive. People agreed to accept IUD insertions and undergo sterilizations for money, not out of free will. This was evident in the fact that poor and lower castes constituted the majority of those who underwent these operations for payment. They went under the knife simply for the money, particularly when faced with destitution during times of drought and famine. Consider also the deeply unequal power relations marshaled for the program. The “community leaders” recruited as motivators were men of influence; they were often local magnates whose “persuasive” power the poor could scarcely be expected to resist. Nor could they have easily defied the state machinery, which the poor routinely experienced as distant and overbearing. The intimidating sight of the district magistrate arriving with mobile vans and health workers in the villages and small towns could not but have wilted the free will of the underprivileged.

Marika Vicziany has shown that the Emergency did not invent coercion. Force was inherent in the pre-Emergency use of financial incentives and disincentives, the employment of motivators, and the mobilization of district officers. Contrary to the “myth” that India was a “soft state” that relied on voluntarism for population control, she shows that the program was coercive.

Even without being explicitly intended, coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor. This was the poisoned fruit of the nature of the regime that came to power in 1947. Instead of enacting and implementing radical land reforms and promoting the overall health and education of subordinate groups by empowering them with resources, the postcolonial elite chose state-directed modernization. Along with industrial growth and the Green Revolution, population control was an outcome of this strategy of change from above. Indian elites believed in it, and they were encouraged and prodded by the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, IPPF, and transnational experts. Together, they exuded the prevalent high-modernist confidence in the social engineering of humanity with scientific data and methods. Such a lens impelled the postcolonial regime to decide that control over reproduction was “a critical battleground in the war against poverty, in which sterilization, pills, and IUDs could be used as weapons.”

Even without being explicitly intended, coercion was inherent in a program designed by international and Indian elites and directed at the poor. This was the poisoned fruit of the nature of the regime that came to power in 1947. Instead of enacting and implementing radical land reforms and promoting the overall health and education of subordinate groups by empowering them with resources, the postcolonial elite chose state-directed modernization.

Thus, even when the 1973 oil crisis tightened the budget allocation for family planning and led to a nationwide reduction in the number of sterilizations, Health Minister Karan Singh remained undaunted. He announced that the government would redouble its efforts and increase payments to those who underwent tubectomies or vasectomies. He struck a different note at the 1974 Bucharest World Population Conference where he memorably declared, “The best contraceptive was development.” But it was empty rhetoric. It did not mean any retreat from aggressive population control to tackle poverty. In April 1975, the Central Family Planning Council passed a resolution that proposed to revitalize the sterilization program with higher financial incentives. The failure in the strategy to fight poverty with population control did not give the government pause but drove it to reinvigorate the sterilization drive. The stage was set for the program to ratchet up its built-in coercive nature by several notches.

This excerpt has been carried courtesy the permission of Gyan Prakash and Penguin Random House India. You can buy Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point here.

Gyan Prakash is the Dayton-Stockton professor of history at Princeton University. He specializes in the history of modern India. He was a member of the influential Subaltern Studies Collective until its dissolution in 2008, and has been a recipient of the Guggenheim and the National Endowment of Humanities fellowships. He is the author of several books, including Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India (1999), the widely acclaimed Mumbai Fables (2010), which was adapted for the film Bombay Velvet (2015), for which he wrote the story and co-wrote the screenplay, and Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point (2018). He lives in Princeton, New Jersey. You can read more about him and his work here.

#population #control #planning #family #government #health #emergency #lockdown #indiragandhi #gandhi #sanjaygandhi #indira #sanjay #india #people #sterilization #world #ensminger #rockefeller #international #nehru #poverty #research #development #asoka #contraceptive #camps #riots #students #controversial #control #president

Comments